Sacramento's LGBTQ History

The Journey Toward Queer Liberation in Sacramento

The roots of the LGBTQ community in California run deep. Some might even say they run deep as gold, as it has been rumored the handkerchief code, widely recognized in queer social settings, got its origins from the square dances of the California Gold Rush.

Whether or not that can be accepted as a hard-and-fast history, what’s undeniable is that our state was the birthplace of queer liberation groups such as the Mattachine Society in 1950, Daughters of Bilitis in 1955 and the Society for Individual Rights (SIR) in 1964, all of which spurred national chapters and widespread activism.

And as for Sacramento itself, the vibrant and flourishing LGBTQ community you see today has its own storied history, advanced at every turn by courageous thought leaders and trailblazers who fought to get our city’s queer people out of the closet and into the sun.

2013 Pride March photo courtesy Outword Magazine.

2013 Pride March photo courtesy Outword Magazine.

Stoking a Movement

One of the earliest activists to champion LGBTQ people in Sacramento was Rick Stokes, a teacher and lawyer who dedicated his life to advancing equality for queer people. Stokes, a member of SIR, was inspired to launch his own group in Sacramento to create a sense of community for LGBTQ people who were mostly keeping their identities a secret.

The first meeting of Stokes’ group, Americans for Responsible Citizenship (ARC), was held in 1965 and attracted just six members. But once the word was out, it became clear there was a larger demand for ARC in Sacramento, and its membership swelled so quickly that, when the group staged a New Year’s Eve ball later that year, more than 180 people showed up. After forming an official constitution with a stated mission to operate as a civil rights organization, ARC launched its own newsletter, ARC News (sometimes referred to as ARC Journal or Archer), to further build a queer community while advancing education for the wider community.

Although Stokes relocated to San Francisco by the early ‘70s, his work continued to center queer representation and equality in both society and legislature following his move from the city. He even famously ran against Harvey Milk for San Francisco City Supervisor in 1977 as “the other gay candidate.” But Sacramento will always be proud to say that Stokes began building his legacy right here, and our community is all the better for it.

Sac State Society for Homosexual Freedom

In 1970, a Sacramento State student named George Raya officially requested that the Society for Homosexual Freedom (SHF) be recognized by Associated Students, Inc. (ASI), the organization responsible for granting student clubs official status on campus. Raya, a member of the student senate, had just come out as gay the previous year and was a founding member of SHF, a group designed to promote unity and acceptance among queer and straight youth.

However, Raya’s request to formally allow the group on campus was met with fierce resistance and controversy. Otto Butz, acting president for Sac State at the time, rejected the charter and prevented ASI from recognizing SHF as an official organization. While many groups both on campus and in the wider community voiced their support for the formation of SHF, there was equal support for Butz’s decision to reject it. Opponents to SHF claimed that, because of California’s then-existing laws against homosexuality and sodomy, allowing the group to gather would be an implicit condoning of illegal acts.

Raya—along with other queer students, allies and community activists—didn’t back down. Instead, he co-wrote an open letter with the student senate and published it in the campus newspaper, State Hornet. The student senate, with representation from Sac State alumnus John Poswall, then filed a lawsuit against the university and its board. They alleged that their first amendment rights were being violated by the college—and the court agreed. Judge William Gallagher ruled that the club was not inherently violating state law, and therefore, opposition to the club was rooted in prejudice and fear of homosexual activity between club members.

On February 19, 1971, SHF was officially recognized on-campus by Sacramento State, and the group went on to host events that attracted prominent LGBTQ icons like Allen Ginsberg. Following his graduation, Raya moved to San Francisco and became involved with SIR, which ultimately tasked him with returning to Sacramento and lobbying for a repeal of the state’s sodomy laws.

Once again, Raya was victorious. In 1975, Assembly Bill 489 was signed into law by Governor Brown, marking the end of criminalization for sodomy and oral copulation. Two years later in 1977, Raya was invited by the National LGBTQ Task Force (then the National Gay Task Force) to attend a discussion of LGBTQ rights at the White House.

Sacramento Pride

Similar to the way New York Pride–and the national Pride movement–were spurned by acts of revolution, the first iteration of Sacramento Pride was a response to the police raid on the Upstairs/Downstairs gay disco in March 1979.

Just a few months later, on June 17, 1979, Sacramento Pride held its first parade. More than 500 queer people and allies gathered for a march across Midtown that was equal parts celebration and demonstration. Soon after, in January 1980, local activists braved freezing weather conditions to stage the March on Sacramento for Lesbian and Gay Rights, which served to cement the area’s status as an epicenter of politically focused queer liberation.

By June of 1980, the second Sacramento Pride parade doubled the size of its original crowd, and Mayor Phil Isenberg formally declared the week of June 15-22 Sacramento Gay Pride Week.

More than 40 years later, Sacramento Pride retains its roots as an activism-oriented demonstration of culture and community, drawing an estimated 22,000 visitors every year.

Reaching New & Lavender Heights

Since the beginning of the queer liberation movement in Sacramento, one area at the intersection of 20th and K Streets Midtown emerged as a neighborhood haven due to its high concentration of LGBTQ venues, businesses and resources. Today, that area is known as Lavender Heights.

Lamppost photo courtesy of Rainbow Chamber of Commerce; Group Lavender Heights photo courtesy of Outword Magazine.

The nickname “Lavender Heights” began to circulate in the mid-1970s, albeit unofficially, as more and more queer-friendly businesses emerged in the area. These included the lesbian-owned Lioness Books, Christie’s Elbo Room (now the site of Faces Nightclub, the longest-standing gay club in the city), and the Western (now home to The Depot). The concentration of these businesses, along with a rapidly growing gay population around college campuses, led to the development of LGBTQ focused resources and organizations in the area, too.

Jerry Sloan photo courtesy of Outword Magazine.

The Sacramento LGBT Community Center began in Lavender Heights as the Lambda Community Fund in 1978. After gay activist Rev. Jerry Sloan of Metropolitan Community Church (MCC) successfully sued Rev. Jerry Falwell in 1984 for televised comments Falwell made against MCC, Sloan used a portion of the money awarded to him (which was nearly $9,000) to open the first physical iteration of the SAC Center, Lambda Community Center, in 1986. Though its name has now changed, the organization endures today and continues to provide support and resources to Sacramento’s LGBTQ community.

Rosemary Metrailer photo courtesy of Legends of Courage produced by Dawn Deason/3D Media Solutions.

Rosemary Metrailer, the lawyer who successfully represented Sloan in court, was herself the founder of an LGBTQ organization: the Sacramento Area Career Women's Network, which Metrailer established in June 1984 after meeting other lesbian professionals who expressed a desire for a professional referral and networking forum. Events were often educational and focused on networking and were hosted in private spaces to allow free expression without fear of professional or personal consequences. Metrailer says that between 1984-2007, when the organization was dissolved, more than 500 cumulative members had benefited from SACWN.

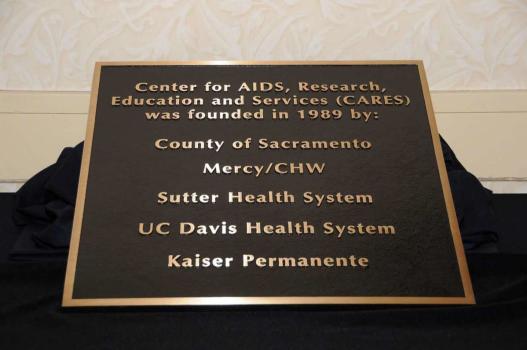

CARES Clinic Dedication Plaque photo courtesy of Outword Magazine.

In 1989, the Center for AIDS Research, Education & Services (CARES Clinic) was established to provide critical support for people living with HIV/AIDS. CARES continued its mission for years, and in 2017, evolved into One Community Health, where HIV patients, their families and the community at large can receive affordable and accessible healthcare.

Additionally, the Lavender Library was founded by eight community members in 1998 as a research and information institution for queer people in Sacramento, and continues operation today on 21st Street. The Rainbow Chamber of Commerce followed in 2001 to unify and support LGBTQ businesses, as well as to foster a more equitable business climate.

Recognizing the impact and contributions of the LGBTQ community on the Lavender Heights area, former Sacramento City Council member, and the first openly gay member, Steve Hansen championed the city’s official recognition and naming of the district. The name Lavender Heights became official in 2015, an achievement memorialized by the unveiling of the rainbow crosswalk at the intersection of 20th and K Street.

New resources for LGBTQ people continue to emerge in the Lavender Heights district, most recently with the opening of the Lavender Courtyard in July 2022 to provide compassionate and affordable housing to LGBTQ seniors.

LGBTQ Welcome

Guide

Our LGBTQ Welcome Guide has essential insider tips and highlights for travelers and locals alike. Inside our guide you will find things to do, places to see, businesses to support, and so much more.

Check out the guideLGBTQ Welcome

Guide

Our LGBTQ Welcome Guide has essential insider tips and highlights for travelers and locals alike. Inside our guide you will find things to do, places to see, businesses to support, and so much more.

Check out the guide